All India Judicial Service

All India Judicial Service

Syllabus: General Studies II- Polity and Governance

Sub-topic:

- Constitutional Framework: AIJS and Article 312.

- Separation of Powers: Implications on Judiciary Independence.

- National Judicial Commission: Oversight in AIJS Recruitment

Tags:

#AllIndiaJudicialService #AIJS #JudicialReforms #LegalSystem #UPSC #LawCommission #JudicialOfficers #ConstitutionalFramework #LegalEducation #JudiciaryIndependence #MeritBasedSelection #CasePendency #Representation #Transparency #JudicialStandards

Why in the News?

The proposal for the creation of an All India Judicial Service (AIJS) has re-gained attention, with President Droupadi Murmu suggesting the need for the judicial service during the Constitution Day celebrations.

| AIJS (All India Judicial Service), envisages a cadre of judicial officers recruited through a national-level exam and aims to revolutionize the lower judiciary. This is embedded in the constitutional framework and presents both promises and challenges for India’s legal system. |

Historical Perspective:

| 1950: The Constitution of India in its original form did not carry any provision on AIJS but the Drafting committee, at last, came out with Article 235 which puts the lower judiciary under the control of the High Court.

1958: The Law Commission of India proposes the idea of AIJS in its 14th report. 1976: After the Swaran Singh Committee’s recommendations, Article 312 is modified to include judicial services, excluding anyone below the rank of district judge. 1961, 1963, 1965: Chief Justice Conferences favour the creation of AIJS, but face opposition from some states and High Courts. 1993: The Supreme Court of India also endorsed the same in the All India Judges Association vs. Union of India case laying down that AIJS should be set up. This means no constitutional amendment will be required for the establishment of AIJS. Present: The proposal for AIJS gains renewed attention, with discussions on addressing judicial vacancies, improving recruitment efficiency, and ensuring diverse representation. |

Need for AIJS:

The pressing issues prompting the consideration of AIJS include:

- Vacancies and Recruitment Delays:

- With approximately 5,400 vacant positions in the lower judiciary, delayed recruitment processes contribute to a staggering backlog of 2.78 crore cases.

- Quality of Judicial Officers:

- The declining quality of judicial officers jeopardizes justice delivery, increasing case pendency, and impacting the competence of the higher judiciary.

- Financial Constraints:

- State judicial services’ unattractiveness to top talents due to financial constraints necessitates a shift toward a more lucrative and competitive service.

- Training and Specialization:

- Inadequate training facilities in state institutes demand the establishment of specialized institutions for comprehensive legal education and training.

- Subjectivity and Nepotism:

- Addressing concerns of subjectivity, corruption, and nepotism in the current appointment processes is vital for a transparent and impartial recruitment system.

Objections to AIJS:

- Separation of Powers:

- Transferring control to the Union government may undermine the independence of the judiciary, diluting the separation of powers.

- Legal Education Standards:

- AIJS may not effectively address the mismanagement and lack of standards in legal education, impacting the quality of legal research and scholarship.

- Language Barriers:

- Local language challenges may hinder AIJS officers in adapting to state-level practices, particularly in districts where courts transact business in the state language.

- Quota and Promotional Avenues:

- AIJS could limit promotional avenues for officers entering through state services, affecting the overall composition of state judicial services.

Challenges for the creation of the AIJS:

- A major issue would be that the posted judicial officer would be unaware of the local laws and customs which are important in deciding cases, particularly in matrimonial testamentary or property cases where final outcomes are determined by local customs.

- The vacancy is not uniform across all the states. Further, most of the vacancies are present at the subordinate level and not at the level of district judges. Therefore, AIJS which is only for the recruitment of district judges is not the solution for vacancies.

- A lot of coaching institutes would start flourishing across the country and hence education would be commercialized.

- Many communities who benefit from state quotas may not get any reservation by the Central Government after the creation of AIJS.

Benefits of AIJS:

- Accountability and Transparency:

- A career in judicial service enhances accountability and transparency, fostering a more professional and equitable judiciary.

- Objective Recruitment:

- Conducting open competitive exams reduces subjectivity in the recruitment process, ensuring a merit-based selection of judicial officers.

- Attracting the Best Talent:

- AIJS attracts the best legal talents, ensuring a steady influx of qualified officers and potentially expediting promotions to High Courts.

- Uniform Justice Dispensation:

- Standardizing adjudication practices across the country addresses disparities in state-level laws, practices, and standards.

- Pendency Reduction:

- Streamlined recruitment guarantees a continuous supply of quality officers, contributing to the reduction of case pendency.

- Representative Character:

- AIJS promotes diversity by drafting trained officers from underrepresented sections, enhancing the representative character of the judiciary.

Way Forward:

- As Niti Aayog’s report suggests, AIJS could play a pivotal role in maintaining high judicial standards.

- The proposal incorporates safeguards to address concerns about the independence of the judiciary and language barriers.

- The establishment of an ‘All India Judicial Commission’ mirrors the UPSC model, emphasizing the autonomy of the subordinate judiciary.

- While concerns persist, AIJS emerges as a critical reform to fortify the foundation of the Indian judiciary.

Expected mains Question:

- Examine the constitutional basis for the All India Judicial Services (AIJS). Discuss the relevance of Article 312 and Article 233, and assess the role of the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) in AIJS recruitment.

Prelims Question:

Which among the following statements are true regarding the AIJS? Choose the correct option:

(a) UPSC’s role is minimal; AIJS is primarily governed by state laws.

(b) Article 233 exclusively governs AIJS, and Article 312 is irrelevant.

(c) Both Article 312 and Article 233 contribute to AIJS, with UPSC playing a crucial role.

(d) AIJS is constitutionally mandated only by state laws, and UPSC’s involvement is discretionary.

Answer: (c) Both Article 312 and Article 233 contribute to AIJS, with UPSC playing a crucial role.

Explanation:

Article 312 of the Indian Constitution empowers the Parliament to create All India Services, including the All India Judicial Services (AIJS). It provides a constitutional basis for a unified recruitment mechanism for judicial officers across states.

Article 233 gives the President of India the power to consult with the state’s Governor and establish rules for the recruitment of persons to the judicial service of the state.

The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) plays a crucial role in conducting examinations for AIJS, ensuring transparency, and maintaining meritocracy in the selection process.

This option captures the interplay between constitutional provisions and the role of the UPSC in the context of AIJS.

Special Category Status

Special Category Status

Why in The News?

Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar reiterated the demand for special status in Bihar, citing its backwardness, huge population, poverty, and lowest per capita income.

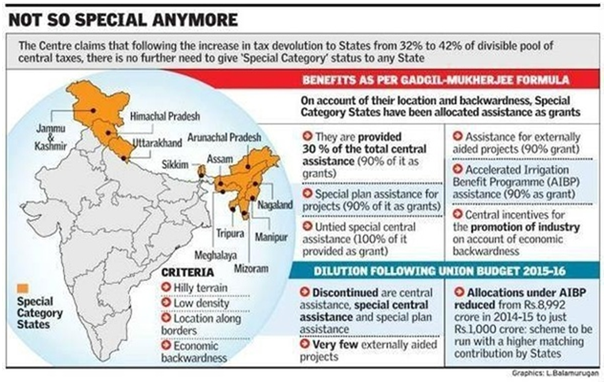

Special Category Status:

- It is a designation conferred by the Central government to states facing socio-economic and geographic disadvantages, aiming to facilitate their development.

Historical Context and Decision-Making:

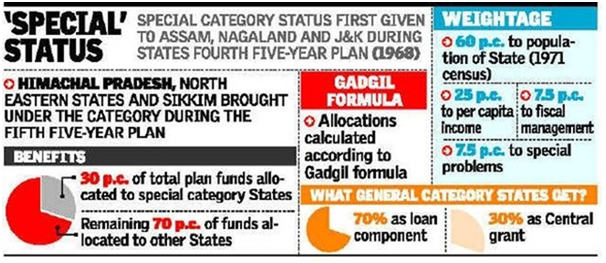

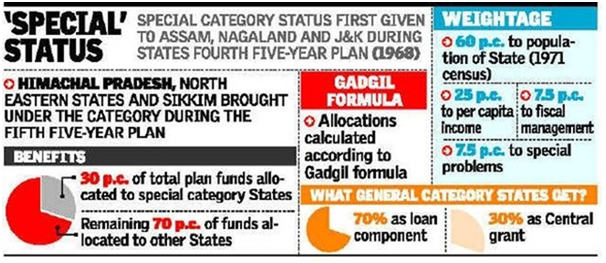

- Origins in 1969 by the Fifth Finance Commission

- Absence in the Constitution

- Aimed at historically disadvantaged states with inherent challenges.

- Jammu and Kashmir (now union territories), Assam, and Nagaland being the pioneering states granted this status under the chairmanship of Mahavir Tyagi

- Initial authority with the National Development Council (NDC)

- Shift to the discretion of the ruling party at the Centre with the advent of NITI Aayog.

- Inclusion of variables like “forest cover” by the 14th Finance Commission

—the classification aimed to address the socio-economic and geographic challenges these states faced.

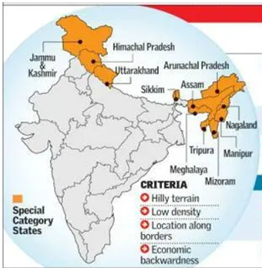

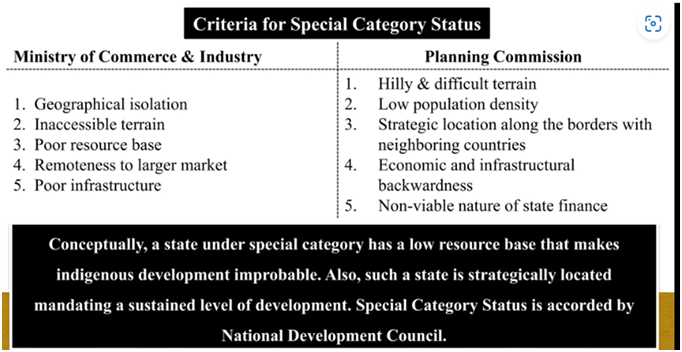

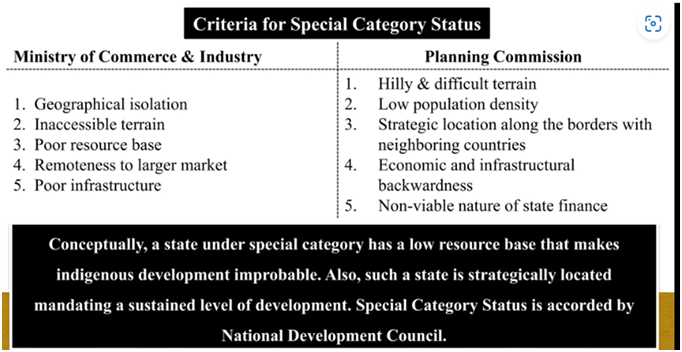

Criteria for Special Category Status:

- Hilly and challenging terrain.

- Strategic border locations.

- Low per capita income and low population density.

- Sizable tribal populations.

- Economic and infrastructure backwardness, and

- Non-viable state finances.

This distinction aims to ensure uniform growth, equality, and inclusive development.

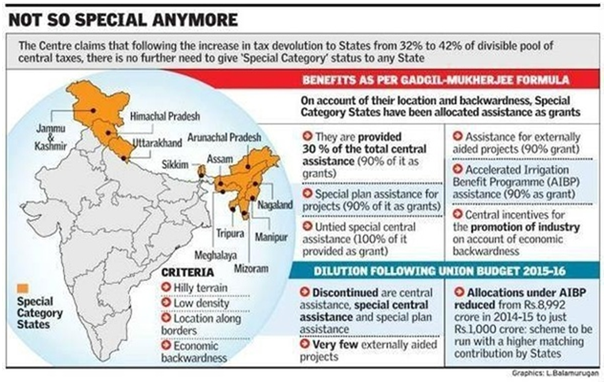

| States currently Holding Special Category Status:

11 states, Assam, Nagaland, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Uttarakhand, and Telangana. |

| Benefits Associated with Special Category Status:

· Central government covering 90% of state expenditures for centrally sponsored programs.

|

Financial Assistance:

- Normal Central Assistance (NCA), Additional Central Assistance (ACA), Special Central Assistance (SCA)

- Preferential allocation: 30% to special category states, 70% to others

- Composition of assistance: 90% grants and 10% loans for special category states

Additional Concessions:

- Excise and customs duties, income tax rates, corporate tax rates

Specific Assistance:

- Targeted programs for hill areas, tribal sub-plans, and border areas

Evolution of Central Approach:

- Role of NITI Aayog and 14th Finance Commission

- Increased devolution of divisible pool to all states

- Controversy around demand for Special Category Status by certain states.

Recent Developments and Controversies:

- Demands from states like Bihar and Andhra Pradesh

- Clarifications from the 15th Finance Commission

- Shift in the narrative post-14th Finance Commission recommendations

Understanding India’s Federal Structure: India, a “union of states” with 29 states and 7 union territories, periodically allocates a portion of the central government’s revenues to these entities based on recommendations from the Finance Commission.

Constitutional Provision: Article 275 of the Indian Constitution empowers the central government to provide additional financial assistance to any state beyond the Finance Commission’s recommendations. Currently, 11 states hold the Special Category Status, while five others seek this designation.

Benefits Associated with Special Category Status: The advantages conferred on states with SCS include:

- Central government covering 90% of state expenditures for centrally sponsored programs.

- 10% provided as a zero-interest loan.

- Special consideration in government funding applications.

- Reductions in excise taxes to attract businesses.

- Access to 30% of the total federal budget.

- Programs for debt reduction and debt exchange.

- Exemption from various taxes to encourage investment.

Top of Form

Concerns:

- Dilution of Benefits:

Special status to new states may dilute benefits as broader distribution might reduce assistance and privileges.

- Modest Current Benefits:

Existing system benefits are deemed modest as support may not sufficiently address state challenges.

Conclusion:

- Abolition of Special Category Status:

The 14th Finance Commission abolished “special category status, to promote equitable resource distribution and balanced development.

- Increased State’s Share of Tax Receipts:

State’s share has increased from 32% to 42% since 2015,to Enhance state financial base for development and bridge resource gaps.

Top of Form

Prelims Question:

Consider the following statements regarding the Special Category Status in India:

- The concept of Special Category Status originated in 1969 under the recommendations of the Sixth Finance Commission.

- According to the information provided, “forest cover” was introduced as a variable impacting the classification of states under Special Category Status by the 14th Finance Commission.

- The criteria for Special Category Status include high population density, economic and infrastructure backwardness, and viable state finances.

Which of the statements is/are correct?

a) Only One Statement.

b) Only Two Statements.

c) Only Three Statements.

d) None.

Expected Mains Question?

Critically evaluate the concerns associated with granting Special Category Status to states, especially in light of potential dilution of benefits. Discuss the counterarguments regarding the modest benefits under the current system.